Coconut

| Coconut Palm | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Coconut Palm (Cocos nucifera) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| (unranked): | Angiosperms |

| (unranked): | Monocots[1] |

| (unranked): | Commelinids |

| Order: | Arecales |

| Family: | Arecaceae |

| Subfamily: | Arecoideae |

| Tribe: | Cocoeae |

| Genus: | Cocos |

| Species: | C. nucifera |

| Binomial name | |

| Cocos nucifera L. |

|

The coconut (Cocos nucifera) is an important member of the family Arecaceae (palm family). It is the only accepted species in the genus Cocos,[2] and is a large palm, growing up to 30 m tall, with pinnate leaves 4–6 m long, and pinnae 60–90 cm long; old leaves break away cleanly, leaving the trunk smooth. The term coconut can refer to the entire coconut palm, the seed, or the fruit, which is not a botanical nut. The spelling cocoanut is an old-fashioned form of the word.[3]

The coconut palm is grown throughout the tropics for decoration, as well as for its many culinary and non-culinary uses; virtually every part of the coconut palm can be utilized by humans in some manner. In cooler climates (but not less than USDA Zone 9), a similar palm, the queen palm (Syagrus romanzoffiana), is used in landscaping. Its fruits are very similar to the coconut, but much smaller. The queen palm was originally classified in the genus Cocos along with the coconut, but was later reclassified in Syagrus. A recently discovered palm, Beccariophoenix alfredii from Madagascar, is nearly identical to the coconut, and more so than the queen palm. It is cold-hardy, and produces a coconut lookalike in cooler areas.[4]

The coconut has spread across much of the tropics, probably aided in many cases by seafaring people. Coconut fruit in the wild is light, buoyant and highly water resistant, and evolved to disperse significant distances via marine currents.[5] Fruit collected from the sea as far north as Norway are viable. In the Hawaiian Islands, the coconut is regarded as a Polynesian introduction, first brought to the islands by early Polynesian voyagers from their homelands in Oceania. They are now almost ubiquitous between 26°N and 26°S except for the interiors of Africa and South America.

The flowers of the coconut palm are polygamomonoecious, with both male and female flowers in the same inflorescence. Flowering occurs continuously. Coconut palms are believed to be largely cross-pollinated, although some dwarf varieties are self-pollinating. The meat of the coconut is the edible endosperm, located on the inner surface of the shell. Inside the endosperm layer, coconuts contain an edible clear liquid that is sweet, salty, or both.

The Indian state of Kerala is known as the Land of coconuts. The name derives from "Kera" (the coconut tree) and "Alam" ( "place" or "earth"). Kerala has beaches fringed by coconut trees, a dense network of waterways, flanked by green palm groves and cultivated fields. Coconuts form a part of daily diet, the oil is used for cooking, coir is used for furnishing, decorating, etc.

Coconuts received the name from Portuguese explorers, the sailors of Vasco da Gama in India, who first brought them to Europe. The brown and hairy surface of coconuts reminded them of a ghost or witch called Coco.[6] Before it was called nux indica, a name given by Marco Polo in 1280 while in Sumatra, taken from the Arabs who called it جوز هندي jawz hindī. Both names translate to "Indian nut." When coconuts arrived in England, they retained the coco name and nut was added.

Contents |

Origins

The origins of this plant are the subject of debate.

- Most authorities claim it is native to South Asia (particularly the Ganges Delta), while others claim its origin is in northwestern South America.

- Fossil records from New Zealand indicate that small, coconut-like plants grew there as long as 15 million years ago.

- Even older fossils have been uncovered in Karnataka, Rajasthan, Thennai in Kerala on the banks of River Palar, Then-pennai, Thamirabharani, Cauvery and Mountain sides at Kerala borders, Konaseema-Andhra Pradesh, Maharashtra (India)

- The oldest known so far in Khulna, Bangladesh.

- Mention is made of coconuts in the 2nd–1st centuries BC in the Mahawamsa of Sri Lanka. The later Culawamsa states that King Aggabodhi I (575–608) planted a coconut garden of 3 yojanas length, possibly the earliest recorded coconut plantation.

Etymology

The OED states: "Portuguese and Spanish authors of the 16th c. agree in identifying the word with Portuguese and Spanish coco 'grinning face, grin, grimace', also 'bugbear, scarecrow', cognate with cocar 'to grin, make a grimace'; the name being said to refer to the face-like appearance of the base of the shell, with its three holes. Historical evidence favors the European origin of the name, for there is nothing similar in any of the languages of India, where the Portuguese first found the fruit; and indeed Barbosa, Barros, and Garcia, in mentioning the Malayalam name tenga, and Canarese narle, expressly say 'we call these fruits quoquos', 'our people have given it the name of coco', 'that which we call coco, and the Malabars temga'."

Natural habitat

The coconut palm thrives on sandy soils and is highly tolerant of salinity. It prefers areas with abundant sunlight and regular rainfall (150 cm to 250 cm annually), which makes colonizing shorelines of the tropics relatively straightforward.[7] Coconuts also need high humidity (70–80%+) for optimum growth, which is why they are rarely seen in areas with low humidity, like the Mediterranean, even where temperatures are high enough (regularly above 24°C or 75.2°F).

Coconut palms require warm conditions for successful growth, and are intolerant of cold weather. Optimum growth is with a mean annual temperature of 27 °C (81 °F), and growth is reduced below 21 °C (70 °F). Some seasonal variation is tolerated, with good growth where mean summer temperatures are between 28–37 °C (82–99 °F), and survival as long as winter temperatures are above 4–12 °C (39–54 °F); they will survive brief drops to 0 °C (32 °F). Severe frost is usually fatal, although they have been known to recover from temperatures of −4 °C (24.8 °F).[7] They may grow but not fruit properly in areas where there is not sufficient warmth, like Bermuda.

The conditions required for coconut trees to grow without any care are:

- mean daily temperature above 12-13 °C every day of the year

- 50 year low temperature above freezing

- mean yearly rainfall above 1000 mm

- no or very little overhead canopy, since even small trees require a lot of sun

The main limiting factor is that most locations which satisfy the first three requirements do not satisfy the fourth, except near the coast where the sandy soil and salt spray limit the growth of most other trees (Palmtalk[8]).

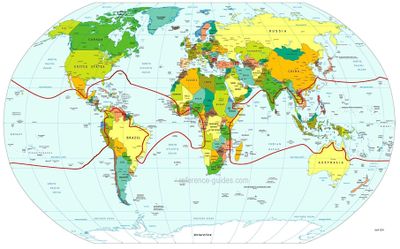

The range of the natural habitat of the coconut palm tree is delineated by the red line in map C1 to the right (based on information in Werth 1933,[9] slightly modified by Niklas Jonsson).

Cultivation

Coconut trees are very hard to establish in dry climates, and cannot grow there without frequent irrigation; in drought conditions, the new leaves do not open well, and older leaves may become desiccated; fruit also tends to be shed.[7]

Coconut palms are grown in more than 80 countries of the world, with a total production of 61 million tonnes per year.[10]

| Top ten coconut producers — 19 December 2009 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | Production (tonnes) | Footnote | ||

| 19,500,000 | * | |||

| 15,319,500 | ||||

| 10,894,000 | ||||

| 2,759,044 | ||||

| 2,200,000 | F | |||

| 1,721,640 | F | |||

| 1,246,400 | F | |||

| 1,086,000 | A | |||

| 677,000 | F | |||

| 555,120 | ||||

| 370,000 | F | |||

| World | 54,716,444 | A | ||

| No symbol = official figure, P = official figure, F = FAO estimate, * = Unofficial/Semi-official/mirror data, C = Calculated figure, A = Aggregate (may include official, semi-official or estimates); |

||||

Harvesting

In some parts of the world (Thailand and Malaysia), trained pig-tailed macaques are used to harvest coconuts. Training schools for pig-tailed macaques still exist both in southern Thailand, and in the Malaysian state of Kelantan.[11] Competitions are held each year to find the fastest harvester.

Pests and diseases

Diseases

Coconuts are susceptible to the phytoplasma disease Lethal Yellowing. One recently selected cultivar, 'Maypan', has been bred for resistance to this disease.

Pests

The coconut palm is damaged by the larvae of many Lepidoptera (butterfly and moth) species which feed on it, including Batrachedra spp: B. arenosella, B. atriloqua (feeds exclusively on Cocos nucifera), B. mathesoni (feeds exclusively on Cocos nucifera), and B. nuciferae.

Brontispa longissima (the "coconut leaf beetle") feeds on young leaves and damages seedlings and mature coconut palms. On September 27, 2007, Philippines' Metro Manila and 26 provinces were quarantined due to having been infested with this pest (to save the $800-million Philippine coconut industry).[12]

The fruit may also be damaged by eriophyid coconut mites (Eriophyes guerreronis). This mite infests coconut plantations, and is devastating: it can destroy up to 90% of coconut production. The immature nuts are infested and desapped by larvae staying in the portion covered by the perianth of the immature nut; the nuts then drop off or survive deformed. Spraying with wettable sulfur 0.4% or with neem-based pesticides can give some relief, but is cumbersome and labour intensive.

In Kerala the main pests of coconut are the coconut mite, the rhinoceros beetle, the red Palm weevil and the coconut leaf caterpillar. Research on this topic has as of 2009[update] produced no results, and researchers from the Kerala Agricultural University and the Central Plantation Crop Research Institute, Kasaragode are still searching for a cure. The Krishi Vigyan Kendra, Kannur under Kerala Agricultural University has developed an innovative extension approach called compact area group approach (CAGA) to combat coconut mites.

India

Traditional areas of coconut cultivation in India are the states of Kerala,Tamil Nadu, Karnataka,Goa, Andhra Pradesh, Orissa, West Bengal, Pondicherry, Maharashtra and Islands of Lakshadweep and Andaman and Nicobar.

Kerala is the largest coconut growing state in India, and is famous for the most tender coconuts in India. They are also famous for the coconut-based products like tender coconut water, copra, coconut oil, coconut cake, coconut toddy, coconut shell-based products, coconut wood-based products, coconut leaves, and coir pith.

Four southern states put together account for 92% of the total production in the country (Kerala 45.22%, Tamil Nadu 26.56%, Karnataka 10.85%, Andhra Pradesh 8.93% and other states 8.44%).[13]

Coconut is cultivated mainly in the following Indian States

- Kerala (All India Production 45%)

- Tamil Nadu (All India Production 27%)

- Karnataka (All India Production 11%)

- Andhra pradesh (All India Production 9%)

- Other States like Goa, Maharashtra, Orisa and West Bengal

.jpg)

United States of America

The only places in the U.S. where coconut palms can be grown and reproduced outdoors without irrigation are Hawaii, south Florida and the U.S. territories of Puerto Rico and Virgin Islands. Coconut palms will grow from coastal Pinellas County and St. Petersburg southwards on Florida's west coast, and Melbourne southwards on Florida's east coast. The occasional coconut palm is seen north of these areas in favored microclimates in the Tampa and Clearwater metro area and around Cape Canaveral, as well as the Orlando-Kissimmee-Daytona Beach metro area. They may likewise be grown in favored microclimates in the Rio Grande Valley area of Deep South Texas near Brownsville and on the upper northeast Texas Coast at Galveston Island. They may reach fruiting maturity, but are damaged or killed by the occasional winter freezes in these areas. Most of the coconut palms, even full grown specimens, in central Florida that were not adjacent to water were killed by the freeze event in January 2010. Even those on the water were damaged, but are recovering. While coconut palms flourish in south Florida, unusually bitter cold snaps can kill or injure coconut palms there as well. Only the Florida Keys and the coastlines provide safe havens from the cold for growing coconut palms on the U.S. mainland. The farthest north in the United States a coconut palm has been known to grow outdoors is in Newport Beach, California along the Pacific Coast Highway. For coconut palms to survive in Southern California, they need sandy soil and minimal water in the winter to prevent root rot, and would benefit from root heating coils.

Middle East

The main coconut producing area in the Middle East is the Dhofar region of Oman. In particular, the area around Salalah maintains large coconut plantations similar to those found across the Arabian Sea. The large coconut groves of Dhofar were mentioned by the medieval Moroccan traveller Ibn Battuta in his writings, known as Al Rihla.[14] This is possible due to an annual rainy season known locally as Khareef.

Coconuts also are increasingly grown for decorative purposes along the coasts of the UAE and Saudi Arabia with the help of irrigation. The UAE have, however, imposed strict laws on mature coconut tree imports from other countries to reduce the spread of pests to other native palm trees, such as the date palm.[15]

Plant

Fruit

| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |

|---|---|

| Energy | 1,481 kJ (354 kcal) |

| Carbohydrates | 15.23 g |

| Sugars | 6.23 g |

| Dietary fiber | 9.0 g |

| Fat | 33.49 g |

| saturated | 29.70 g |

| monounsaturated | 1.43 g |

| polyunsaturated | 0.37 g |

| Protein | 3.3 g |

| Thiamine (Vit. B1) | 0.066 mg (5%) |

| Riboflavin (Vit. B2) | 0.02 mg (1%) |

| Niacin (Vit. B3) | 0.54 mg (4%) |

| Pantothenic acid (B5) | 0.300 mg (6%) |

| Vitamin B6 | 0.054 mg (4%) |

| Folate (Vit. B9) | 26 μg (7%) |

| Vitamin C | 3.3 mg (6%) |

| Calcium | 14 mg (1%) |

| Iron | 2.43 mg (19%) |

| Magnesium | 32 mg (9%) |

| Phosphorus | 113 mg (16%) |

| Potassium | 356 mg (8%) |

| Zinc | 1.1 mg (11%) |

| Percentages are relative to US recommendations for adults. Source: USDA Nutrient database |

|

Botanically the coconut fruit is a drupe, not a true nut.[16] Like other fruits it has three layers: exocarp, mesocarp, and endocarp. The exocarp and mesocarp make up the husk of the coconut. Coconuts sold in the shops of non-tropical countries often have had the exocarp (outermost layer) removed. The mesoocarp or "shell" thus exposed is the hardest part of the coconut, and is composed of fibers called coir which have many traditional and commercial uses. The shell has three germination pores (stoma) or eyes that are clearly visible on its outside surface once the husk is removed.

Seed

Within the shell is a single seed. When the seed germinates, the root (radicle) of its embryo pushes out through one of the eyes of the shell. The outermost layer of the seed, the testa, adheres to the inside of the shell. In a mature coconut, a thick albuminous endosperm adheres to the inside of the testa. This endosperm or meat is the white and fleshy edible part of the coconut. Coconuts sold with a small portion of the husk cut away are immature, and contain coconut water rather than meat.

Although coconut meat contains less fat than many oilseeds and nuts such as almonds, it is noted for its high amount of medium-chain saturated fat.[17] About 90% of the fat found in coconut meat is saturated, a proportion exceeding that of foods such as lard, butter, and tallow. There has been some debate as to whether or not the saturated fat in coconuts is less unhealthy than other forms of saturated fat (see coconut oil). Like most nut meats, coconut meat contains less sugar and more protein than popular fruits such as bananas, apples and oranges. It is relatively high in minerals such as iron, phosphorus and zinc.

The endosperm surrounds a hollow interior space, filled with air and often a liquid referred to as coconut water (distinct from coconut milk). Young coconuts used for coconut water are called tender coconuts: when the coconut is still green, the endosperm inside is thin and tender, and is often eaten as a snack, but the main reason to pick the fruit at this stage is to drink its water. The water of a tender coconut is liquid endosperm. It is sweet (mild) with an aerated feel when cut fresh. Depending on its size a tender contains 300 to 1,000 ml of coconut water.

The meat in a young coconut is softer and more gelatinous than a mature coconut, so much so, that it is sometimes known as coconut jelly. When the coconut has ripened and the outer husk has turned brown, a few months later, it will fall from the palm of its own accord. At that time the endosperm has thickened and hardened, while the coconut water has become somewhat bitter.

When the coconut fruit is still green, the husk is very hard, but green coconuts only fall if they have been attacked by molds, etc. By the time the coconut naturally falls, the husk has become brown, the coir has become drier and softer, and the coconut is less likely to cause damage when it drops, although there have been instances of coconuts falling from palms and injuring people, and claims of some fatalities. This was the subject of a paper published in 1984 that won the Ig Nobel Prize in 2001. Falling coconut deaths are often used as a comparison to shark attacks; the claim is often made that a person is more likely to be killed by a falling coconut than by a shark, yet, there is no evidence of people ever being killed in this manner.[18]

When viewed on end, the endocarp and germination pores give the fruit the appearance of a coco (also Côca), a Portuguese word for a scary witch from Portuguese folklore, that used to be represented as a carved vegetable lantern, hence the name of the fruit.[19] The specific name nucifera is Latin for nut-bearing.

A small number of writings about coconut mention the existence of the coconut pearl due to the rarity of the gem.[20] Reginald[20] mentions in his book a few publishings whose author purposely avoided discussion about the vegetable-gem.

The shell composition is shown in the tables below.

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Roots

Unlike some other plants, the palm tree has neither tap root nor root hairs; but has a fibrous root system.[21]

Inflorescence

On the same inflorescence, the palm produces both the female and male flowers; thus the palm is monoecious.[21]

Uses

The coconut palm yields up to 75 fruits per year. Nearly all parts of the palm are useful, and it has significant economic value.

Coconuts' versatility is sometimes noted in its naming. In Sanskrit it is kalpa vriksha ("the tree which provides all the necessities of life"). In Malay language, it is pokok seribu guna ("the tree of a thousand uses"). In the Philippines, the coconut is commonly the "Tree of Life".

Flower

Coconut Flower and Kerala Marriage

In Kerala in South India, coconut flowers must be present during a marriage ceremony. The flowers are inserted into a barrel of unhusked rice (paddy) and placed within the sight of the wedding ceremony.

Husk

In Thailand, the coconut husk is used as a potting medium to produce healthy forest tree saplings. The process of husk extraction from the coir bypasses the retting process, using a custom-built coconut husk extractor designed by ASEAN-Canada Forest Tree Seed Centre (ACFTSC) in 1986. Fresh husks contains more tannin than old husks. Tannin produces negative effects on sapling growth.[22]

In India, the coconut husk is used in the manufacture of coir, which is subsequently used in the production of rope, as well as household products like door mats and sacks.

Shell

In India, coconut shells are used as bowls and in the manufacture of various crafts products, including buttons. In parts of South India, the shell and husk are burned for smoke to repel mosquitoes.

Culinary

Culinary uses of the various parts of the coconut include:

- The nut provides oil for cooking and making margarine.

- The white, fleshy part of the seed, the coconut meat, is edible and used fresh or dried in cooking.

Coconut water

- The cavity is filled with coconut water, which is sterile until opened. It mixes easily with blood, so for this reason it was used during World War II in emergency transfusions.[23]

- It contains sugar, fiber, proteins, antioxidants, vitamins and minerals, and provides an isotonic electrolyte balance, making it a nutritious food source. It is used as a refreshing drink throughout the humid tropics, and is used in isotonic sports drinks. It can also be used to make the gelatinous dessert nata de coco. Mature fruits have significantly less liquid than young immature coconuts, barring spoilage.

Coconut milk

- Coconut milk is made by processing grated coconut with hot water or milk, which extracts the oil and aromatic compounds. It should not be confused with coconut water, and has a fat content around 17%. When refrigerated and left to set, coconut cream will rise to the top and separate from the milk. The milk is used to produce virgin coconut oil by controlled heating and removing the oil fraction. Virgin coconut oil is found superior to the oil extracted from copra for cosmetic purposes.

- The leftover fiber from coconut milk production is used as livestock feed.

Toddy and nectar

- The sap derived from incising the flower clusters of the coconut is drunk as neera, or fermented to produce palm alcohol, also known as "toddy" or tuba (Philippines), tuak (Indonesia and Malaysia). The sap can be reduced by boiling to create a sweet syrup or candy, too.

- Coconut nectar is an extract from the young bud, a very rare type of nectar collected and used as morning break drink in the islands of Maldives, and is reputed to have energetic power, keeping the "raamen" (nectar collector) healthy and fit even over 80 or 90 years old. A by-product, a sweet honey-like syrup called dhiyaa hakuru is used as a creamy sugar for desserts.

"Millionaire's Salad" and coconut sprout

- Apical buds of adult plants are edible, and are known as"palm-cabbage" or heart-of-palm. They are considered a rare delicacy, as harvesting the buds kills the palms. Hearts of palm are eaten in salads, sometimes called "millionaire's salad".

- Newly germinated coconuts contain an edible fluff of marshmallow-like consistency called coconut sprout, produced as the endosperm nourishes the developing embryo.

Philippines and Vietnam

- In the Philippines, rice is wrapped in coconut leaves for cooking and subsequent storage; these packets are called puso.

- Coconut milk, also known as gata in the Philippines, and coconut flakes are popularly used for cookings, such as the food like Laing, Ginataan, Bibingka, Coconut Rice, Ube Halaya, Pich Pichi, Palitaw, Cassava Cake and many more.

- In Vietnam, coconut is grown mainly in Ben Tre Province, often called the "land of the coconut". It is used to make candy, caramel and jelly.

- Coconut juice and coconut milk are used, especially in Vietnam's Southern style of cooking, including kho and chè.

India

- In Kerala, many dishes include coconut. The most common way of cooking vegetables is to scrape coconut and then steam the vegetables with coconut and spices after frying in a little oil. Dishes that include scraped coconut are generally referred to as "thoran", while dishes without scraped coconut belong to the class "Mezhukku purratti".

- People from Kerala make "chamandis", which involves grinding the coconut meat with salt, chillies, and whole spices. The "chamandi" is eaten with rice or kanji (rice gruel).

- Coconut meat is used as a snack and is eaten with jaggery or molasses.

- "Puttu" is a culinary delicacy from Kerala, in which layers of coconut alternate with layers of powdered rice, all of which fit into a bamboo stalk. In recent times this has been replaced with steel or aluminium tubes, which is then steamed over a pot.

- Daily at least one coconut "tamil:தேங்காய்" is broken in the middle class families in Tamil Nadu for food.

- Invariably the main side dish served with Idli, Vada, and Dosa is coconut chutney.

- Coconut is mixed and ground with spices for sambar and lunch dishes.

Industrial and commercial use

Coir

- Coir (the fiber from the husk of the coconut) is used in ropes, mats, brushes, caulking boats and as stuffing fiber; it is used in horticulture in potting compost.

- Coir is used in mattresses at Kerala, in India. Tamil Nadu stands first in the manufacture of brown fiber, and is second to Kerala in the fiber production in India. The number of coir industries in Tamil Nadu is 5,399.[24]

Coconut leaves

- Coconut leaves are used for making brooms in India. Guyana as the green of the leaves are stripped away leaving the vein (a wooden-like, thin, long strip) tied together form a broom.

- The leaves provide materials for baskets and roofing thatch.

- Leaves can be woven into roofing or mats.

- Leaves are woven into a basket that can draw well water.

- Two leaves (especially the younger, yellowish shoots) weaved into a tight shell the size of the palm and infill with rice and cooked - also known as "ketupat" in Malay archipelago.

- Dried coconut leaves can be burned to ash, which can be harvested for lime.

- The stiff leaflet midribs can be used to make cooking skewers, kindling arrows, or are bound into bundles, brooms and brushes.

- The mid-rib of the coconut leaf is used as a tongue-cleaner in Kerala.

- In India, particularly in Kerala and Tamil Nadu, the woven coconut leaves are used as 'pandals' (temporary sheds) for the marriage functions.

Copra

Copra is the dried meat of the seed and, after further processing, is a source of low grade coconut oil. Coconut oils are used to make soap.

Plant densities in Vanuatu for copra production are generally 9 meter, allowing a tree density of 100–160 trees per hectare.

Husks and shells

- The husk and shells can be used for fuel and are a source of charcoal.

- Dried half coconut shells with husks are used to buff floors. In the Philippines, it is known as "bunot", and in Jamaica it is simply called "coconut brush"

- "Tempurung" as it is called in Malay language, used as soup dish and if fixed with a handle will become a ladle.

- Activated carbon manufactured from coconut shell is considered superior to those obtained from other sources, mainly because of small macropores structure which renders it more effective for the adsorption of gas and vapor and for the removal of color, oxidants, impurities and odor of compounds.

- Half coconut shells are used in theatre Foley sound effects work, banged together to create the sound effect of a horse's hoofbeats.

- In the Philippines, dried half shells are used as a music instrument in a folk dance called maglalatik, a traditional dance about the conflicts for coconut meat within the Spanish era

- Shirt buttons can be carved out of dried coconut shell. Coconut buttons are often used for Hawaiian Aloha shirts.

- Dried half coconut shells are used as the bodies of musical instruments, including the Chinese yehu and banhu, along with the Vietnamese đàn gáo and Arabo-Turkic rebab.

- In World War II, coastwatcher scout Biuki Gasa was the first of two from the Solomon Islands to reach the shipwrecked, wounded, and exhausted crew of Motor Torpedo Boat PT-109 commanded by future U.S. president John F. Kennedy. Gasa suggested, for lack of paper, delivering by dugout canoe a message inscribed on a husked coconut shell. This coconut was later kept on the president's desk, and is now in the John F. Kennedy Library.

Coconut trunk

- Coconut trunks are used for building small bridges; they are preferred for their straightness, strength and salt resistance. In Kerala (India), coconut trunks are used for house construction.

- Coconut timber comes from the trunk, and is increasingly being used as an ecologically sound substitute for endangered hardwoods. It has applications in furniture and specialized construction, notably in Manila's Coconut Palace.

- Hawaiians hollowed the trunk to form drums, containers, or small canoes.

- The "branches" (leaf petioles) are strong and flexible enough to make a switch. The use of coconut branches in corporal punishment was revived in the Gilbertese community on Choiseul in the Solomon Islands in 2005.[25]

Coconut roots

- The roots are used as a dye, a mouthwash, and a medicine for dysentery. A frayed-out piece of root can also be used as a toothbrush.

Use for worship

- In the Ilocos region of northern Philippines, the Ilokano people fill two halved coconut shells with diket (cooked sweet rice), and place liningta nga itlog (halved boiled egg) on top of it. This ritual is known as niniyogan (niyog means coconut in Ilokano), and is an offering made to the deceased, and one's past ancestors. This accompanies the palagip (prayer to the dead).

- A coconut (Sanskrit: narikela) is an essential element of rituals in Hindu tradition, and often is decorated with bright metal foils and other symbols of auspiciousness.

- It is offered during worship to a Hindu god or goddess. Irrespective of their religious affiliation, fishermen of India often offer it to the rivers and seas in the hopes of having bountiful catches.

- In Hindu wedding ceremonies, a coconut is placed over the opening of a pot, representing a womb.

- Hindus often initiate the beginning of any new activity by breaking a coconut to ensure the blessings of the gods and successful completion of the activity.

- The Hindu goddess of well-being and wealth, Lakshmi, is often shown holding a coconut.[26]

- The coconut has a role in Indian daily life. In South India, for all the functions, where prayer take place, there, the Hindus, keep the coconut and banana, along with other 'Pooja' materials, and break open the coconut and after that only any kind of Pooja / prayers / activities will be started.

- In the Temple Town Palani, before going for the worship of God Murugan, at the foot hills of Palani Hills, for the Ganesha, a coconut will be broken at the place where it is marked for that purpose. Every day, thousands of coconuts are broken, and some devotees break even 108 coconuts at a time as per the prayer.

- In tantric practices, coconuts are sometimes used as substitutes for human skulls.

Decoration

- The Zulu Social Aid and Pleasure Club of New Orleans traditionally throws hand decorated coconuts—the most valuable of Mardi Gras souvenirs—to parade revelers. The "Tramps" began the tradition ca. 1901. In 1987, a "coconut law" was signed by Gov. Edwards exempting from insurance liability any decorated coconut handed from a Zulu float.

Other usages

- Sport fruits are also harvested, primarily in the Philippines, where they are known as macapuno. They are sold in jars as "gelatinous mutant coconut" cut into balls or strands.

- The smell of coconuts comes from the 6-pentyloxan-2-one molecule, known as delta-decalactone in the food and fragrance industry.[27]

- Coconut is also commonly used as a traditional remedy in Pakistan to treat bites from rats.

- The dried calyx of the coconut is used as fuel in wood fired stoves.

- The fresh husk of a brown coconut is also used as a dish sponge or as a body sponge.

- The inners are removed and the cases used to display food, such as fruit, for gifts in traditional rituals.

- The nut is used as a target and prize in the traditional British fairground 'coconut shy' game. The player buys some small balls which he throws as hard as he can at the coconuts which are balanced on sticks. Tha aim is to knock a coconut off the stand and win it.

Shelter and tools

Researchers from the Melbourne Museum in Australia observed the octopus species Amphioctopus marginatus' use of tools, specifically coconut shells, for defense and shelter. The discovery of this behavior, observed in Bali and North Sulawesi in Indonesia between 1998 and 2008, was published in the journal Current Biology in December 2009.[28][29][30] Amphioctopus marginatus is the first invertebrate known to be able to use tools.[29][31]

A coconut can be hollowed out and used as a home for a rodent or small birds. Halved, drained coconuts can also be hung up as bird feeders, and after the flesh has gone, can be filled with fat in winter to attract tits.

Allergies

Food Allergies

Coconut can be a food allergen. It is a top five food allergy in India where coconut is a common food source.[32] On the other hand, food allergies to coconut are considered rare in Australia, the U.K., and U.S.[33] As a result, commercial extracts of coconut are not currently available for skin prick testing in Australia or New Zealand.[34]

Despite a low prevalence of allergies to coconut in the U.S., the U.S. Food and Drug Administration began identifying coconut as a tree nut in October 2006.[33] Based on FDA guidance and federal U.S. law, coconut must be disclosed as an ingredient.[35]

Topical Allergies

Coconut-derived products can cause contact dermatitis. They can be present in cosmetics including some hair shampoos, moisturizers, soaps, cleansers and hand washing liquids. Coconut-derived products known to cause contact dermatitis include: coconut diethanolamide, cocamide sulphate, cocamide DEA, CDEA, Sodium Laureth Sulfate, Sodium Lauroyl Sulfate, Ammonium Laureth Sulfate, Ammonium Lauryl Sulfate, Sodium Lauroyl Sarcosinate, Sodium Cocoyl Sarcosinate, Potassium Coco Hydrolysed Collagan, TEA Triethanolamin Laureth Sulfate, Caprylic/Capric Triglyceride, Also watch TEA compounds (Triethanolamine) Laureth Sulfate, Lauryl or Cocoyl Sarcosime, Disodium Oleamide Sulfocuccina, Laureth Sulfasuccinate & Disodium Dioctyl Sulfosuccinate.[34]

See also

- Coconut Palace - a palace made entirely out of coconut located in the Cultural Center of the Philippines in Manila.

- Coconut candy

- Coconut charcoal

- Coir Board of India

- Maypan coconut palm

- Queen palm Similar palm originally classified in the Cocos genus as well as coconut

- Voanioala gerardii – forest coconut, the closest relative of the modern coconut

- Beccariophoenix alfredii - Closest lookalike to the Coconut, but hardier to cold and frost.

References

- ↑ William J. Hahn (1997), Arecanae: The palms, tolweb.org

- ↑ WCSP, World Checklist of Selected Plant Families Cocos

- ↑ J. Pearsall (ed), ed (1999). "Cocoanut". Concise Oxford Dictionary (tenth ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-860287-1.

- ↑ "Beccariophoenix alfredii". General palm description. http://www.mbpalms.com/ProdView.aspx?prodsku=255.

- ↑ Foale, M. "The Coconut Odyssey: the bounteous possibilities of the tree of life." Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research 2003. Retrieved 2009-05-30.

- ↑ pg481

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Species Profiles for Pacific Island Agroforestry: Cocos nucifera (pdf file)

- ↑ Palmtalk: http://www.palmtalk.org

- ↑ Werth, E. 1933. Distribution, Origin and Cultivation of the Coconut Palm (in periodical: Ber. Deutschen Bot. Ges., vol 51, pp. 301–304) (article translated into English by Dr. Child, R. (Director, Coconut Research Scheme, Lunuwila))

- ↑ Food And Agricultural Organization of United Nations: Economic And Social Department: The Statistical Division

- ↑ Training without Reward: Traditional Training of Pig-tailed Macaques as Coconut Harvesters, Mireille Bertrand, Science 27 January 1967: 155 (3761): 484 – 486

- ↑ Inquirer.net, Beetles infest coconuts in Manila, 26 provinces

- ↑ "Body". Keralaagriculture.gov.in. http://www.keralaagriculture.gov.in/htmle/bankableagriprojects/ph/coconut.htm. Retrieved 2009-12-06.

- ↑ "Medieval Sourcebook: Ibn Battuta: Travels in Asia and Africa 1325–1354". Fordham.edu. 2001-02-21. http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/source/1354-ibnbattuta.html. Retrieved 2009-12-06.

- ↑ "Microsoft Word - Management of the red palm 325-343.doc" (PDF). http://www.pubhort.org/datepalm/datepalm2/datepalm2_38.pdf. Retrieved 2009-12-06.

- ↑ COCONUT, PLANT OF MANY USES, from UCLA course on Economic Botany

- ↑ "Nutrition Facts and Information for Vegetable oil, coconut". Nutritiondata.com. http://www.nutritiondata.com/facts-C00001-01c208C.html. Retrieved 2009-12-06.

- ↑ Are 150 people killed each year by falling coconuts? The Straight Dope, 19 July 2002. Retrieved 19 October 2006.

- ↑ Figueiredo, Cândido. Pequeno Dicionário da Lingua Portuguesa. Livraria Bertrand. Lisboa 1940. (in Portuguese)

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Reginald Child. "Coconuts". 2nd ed. London: Longman Group Ltd. 1974.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 P.K. Thampan. 1981. Handbook on Coconut Palm. Oxford & IBH Publishing Co.

- ↑ Somyos Kijkar. "Handbook: Coconut husk as a potting medium". ASEAN-Canada Forest Tree Seed Centre Project 1991, Muak-Lek, Saraburi, Thailand. ISBN 974-3612-77-1.

- ↑ http://www.resoundinghealth.com/static/Eiseman1954.pdf

- ↑ "Directorate of Industries and Commerce, Government of Tamil Nadu, India". Indcom.tn.gov.in. http://www.indcom.tn.gov.in/coir.htm. Retrieved 2009-12-06.

- ↑ Corporal punishment on the Solomon Islands

- ↑ Dictionary of Hindu Lore and Legend (ISBN 0-500-51088-1) by Anna Dallapiccola

- ↑ Data sheet about delta-decalactone and its properties: http://www.thegoodscentscompany.com/data/rw1013411.html

- ↑ Finn, Julian K.; Tregenza, Tom; Norman, Mark D. (2009). "Defensive tool use in a coconut-carrying octopus". Curr. Biol. 19 (23): R1069–R1070. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2009.10.052. PMID 20064403.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Gelineau, Kristen (2009-12-15). "Aussie scientists find coconut-carrying octopus". The Associated Press. http://www.google.com/hostednews/ap/article/ALeqM5jfq6qUad8oMqjmm0UKjxvMrFGaaAD9CJIGO80. Retrieved 2009-12-15.

- ↑ Harmon, Katherine (2009-12-14). "A tool-wielding octopus? This invertebrate builds armor from coconut halves". Scientific American. http://www.scientificamerican.com/blog/post.cfm?id=a-tool-wielding-octopus-this-invert-2009-12-14.

- ↑ Henderson, Mark (2009-12-15). "Indonesia's veined octopus 'stilt walks' to collect coconut shells". Times Online. http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/news/science/biology_evolution/article6956352.ece.

- ↑ Living with food allergies, [1]; Venugopal P. [2] Food Allergy, Pulmon The Journal of Respiratory Sciences.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 Coconut Allergy, Australasian Society of Clinical Immunology and Allergy, [3]; U.K. Food Standards Agency [4]

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 Coconut Allergy, Australasian Society of Clinical Immunology and Allergy, [5]

- ↑ U.S. FDA, Guidance for Industry A Food Labeling Guide, [6]

External links

- Coconut Varieties Endemic to Sri Lanka

- Coconut Time Line

- Plant Cultures: botany, history and uses of the coconut

- Purdue University crop pages: Cocos nucifera

- Coconut

- Cocos nucifera information from the Hawaiian Ecosystems at Risk project (HEAR)

- Descriptors for Coconut (Cocos nucifera L.)

- Coconut Research Center

- P. Batugal, V. R. Rao and J. Oliver (2005). Coconut Genetic Resources. COGENT (International Coconut Genetic Resources Network) – IPGRI (International Plant Genetic Resources Institute). http://www.bioversityinternational.org/Publications/pubfile.asp?ID_PUB=1112.